Why rights exist but justice remains out of reach for the poor | India News

Justice comes with hidden costs that are already burdened by the perpetual cycle of poverty, a cycle that fetters every step of the day, too acutely felt to be ignored. Rights exist. Legal aid is free for them. However, they do not have the benefit of incurring both the literal and opportunity-related costs associated with recurring court dates. Injustice in any form hurts them more. Some remain under a dark cloud of lack of awareness of their existing rights, while others fear the consequences of claiming them.Poverty not only erodes social status, stunts growth and undermines health, but also robs dignity, hitting the weak most cruelly.When poverty forces people from disadvantaged backgrounds to toil relentless hours in harsh conditions just to ensure their child sees food on his plate, enough to keep hope alive even if he can’t dream of a future, survival becomes the only priority.Poverty strengthens their legs and at the same time pushes them to legal weakness.And when such individuals face any form of injustice, whether unfair accusations, workplace exploitation, evictions, domestic abuse, discrimination, or even sudden legal summons, it takes more than courage to access their own legal rights.

Constitutional commitment versus ground reality

Article 39A of the Constitution of India, introduced by the 42nd Amendment in 1976, obliges the state to provide free legal aid and ensure equal justice to all, to ensure that no person is deprived of justice due to lack of affordability of legal representation.

.

This constitutional approach was institutionalized through the Legal Services Authority Act, 1987, under which the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) was established in 1995 as the central body to implement legal aid programs across the country.The legal aid system in India is structured as a country-wide network, from the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) at the Centre, chaired by a Supreme Court Justice as Patron-in-Chief to the Chief Justice of India, state and district legal services authorities and local taluka bodies. At the grassroots, paralegals act as a bridge between citizens and the justice system, drawing from diverse communities including volunteers, teachers, social workers, anganwadi workers, law students and marginalized groups.

.

The concept is simple but ambitious, justice should reach the doorsteps of the poor.Yet access remains low. Former Chief Justice of India, former Justice Dr Supreme Court of IndiaAnd former Executive Chairman of the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA), Justice Uday Umesh Lalit, in an interview to Sangsad TV, noted after reviewing the countrywide data:“Statistics show that people get legal aid in less than 1% of cases that require a trial. If we look at how many people are below the poverty line, it is inconsistent that only 1% would need legal aid. Either they don’t know it’s their right, or they don’t trust the system.”This single statistic exposes a deep structural contradiction, in a country where millions are eligible for free legal aid only a tiny fraction can access it.Amidst the daily struggle of poverty, many people are unaware of their right to legal aid or free legal services. A roadside vendor described how the police used court cases to intimidate them. He was shocked when asked if legal aid was available free of charge.“I had no idea that legal aid or free legal services existed. I faced a legal problem and I couldn’t get the help I needed because I couldn’t afford it. At that time I felt most helpless. I had to beg others for help and money, I didn’t know if justice would ever come. For a poor person, respect is the most important thing. Even being associated with the court or the police scares us. You know what happens to poor people like us, they rarely get justice, and nobody supports them, making it hard to trust the system. When we go to complain, we are often intimidated, and we have to endure it. At that point, it seems all doors are closed,” he told TOI.

.

Poverty and legal vulnerability: a powerful cycle

According to the latest World Bank data, between 2011-12 and 2022-23, India lifted nearly 269 million people out of extreme poverty, reducing the poverty rate from 27.1% to 5.3%. Yet some 75 million people still live in extreme poverty, facing challenges not only in deprivation of food, health care and education, but also in accessing legal protection and effectively exercising their rights.

.

People living in deprivation often face:

- Non-forfeiture of daily wages for hearing,

- Lack of access to court,

- Absence of identity or property documents,

- Fear of police or authority figures,

- Dependence on informal or exploitative intermediaries,

For many, even receiving a legal notice or court summons can cause panic rather than protection. Without awareness or guidance, such notices can be ignored, not out of disobedience but out of confusion or fear, sometimes with dire legal consequences.Advocate Abhipriya Rai explains, “Poverty is not just an economic condition, it is a legal disability. When a family cannot produce an Aadhaar card, a birth certificate or a caste certificate, they become invisible to the system designed to protect them.”

.

He adds that legal vulnerability operates simultaneously on three levels. “Informational: They don’t know they have rights. Documentary: Even if they do, they lack the paperwork that activates those rights. Representative: Even if they reach a forum, they cannot sustain effective advocacy. Each obstacle compounds the others.”Legal vulnerability therefore does not become a separate condition, but rather a direct extension of economic vulnerability.

The grassroots organizations are the witness

NGO workers who interact daily with marginalized families consistently observe how poverty silently erodes agency and trust.According to Vikas Jha, founder of Bhavisya NGO, poverty often prevents families from believing their grievances are heard. Lack of nutritious food, clean water, health care and quality education undermines both physical and mental resilience. He noted that many children from such backgrounds start working early to support their families, further reducing their chances of awareness of rights or legal remedies.

.

TOI also spoke to Mahendra Singh Rawat, project coordinator at Bhoomi NGO, Delhi, who has worked with underprivileged children in shelters and slum communities for over three years. He highlighted how poverty affects every aspect of a child’s life:“It is not only financial deprivation, but also limits awareness, opportunities, confidence and aspirations. Many parents are daily wage laborers with unstable income. Many children drop out early, and some are pushed into begging or working to support their families”. He also noted that lack of awareness about rights and government schemes, absence of proper documents in some cases and fear of approaching the authorities perpetuates lack of justice among the poor despite the existence of legal aid structures.

.

A Delhi-based cleaner who wished to remain anonymous added: “Daily wage workers like me cannot afford to demand better conditions. Even if it affects our health badly, we cannot quit. Nobody cares. I may be useful to the system, but I am not considered a dignified part of it and I do not feel my voice will be raised.”

Why free legal aid alone is not enough

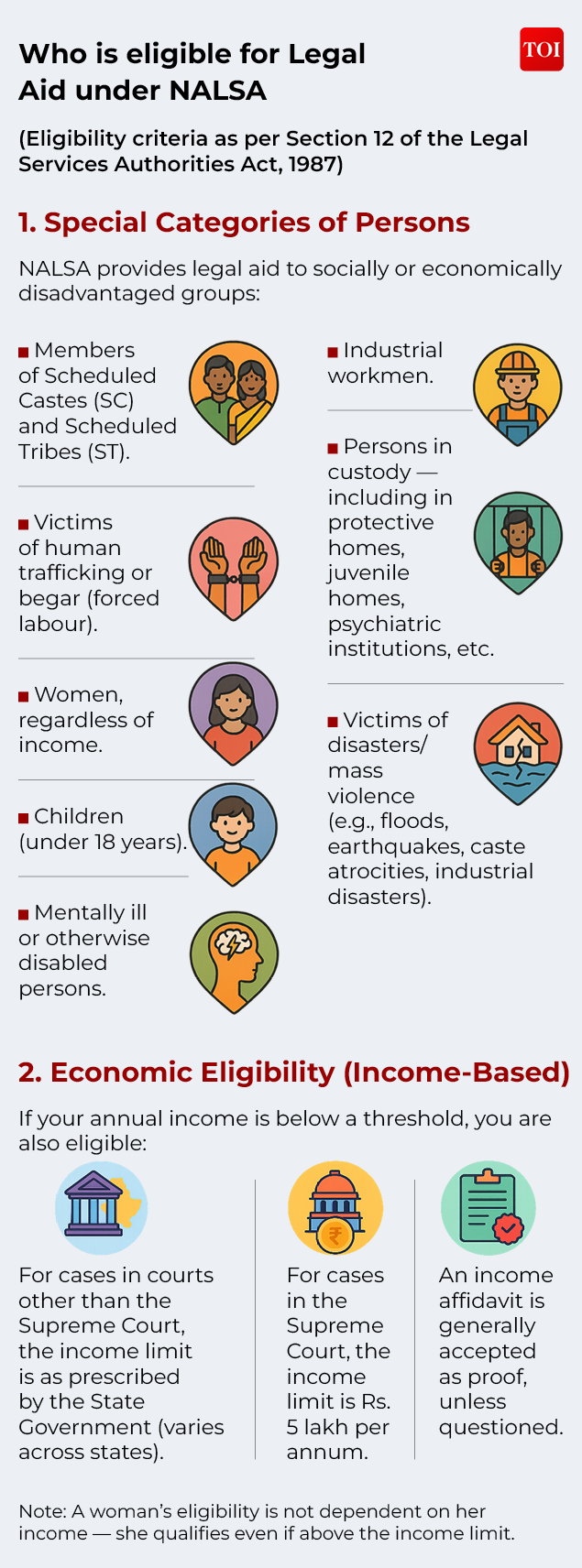

India’s legal aid structure is widely regarded as one of the most comprehensive in the world. Qualifications typically include:

- Individuals below the income limit,

- women and children,

- Scheduled Castes and Tribes,

- disabled person,

- victims of trafficking or disaster,

- industrial workers,

- who are in custody,

.

Services may include legal advice, representation, drafting documents, and mediation, all free of charge.Yet access gaps remain because formal entitlement does not automatically translate into practical accessibility.

Common barriers include:

- Lack of awareness about rights, legal aid structures and eligibility,

- mistrust of state institutions,

- language barrier,

- social stigma,

- procedural complications,

- Perception that free services are inferior,

Hidden costs of litigation

Although legal representation may be free, justice still carries indirect costs:

- Court travel expenses,

- Loss of wages from attending hearings,

- child care arrangements,

- Repeated procedural delays,

Reflecting these hidden costs, Adv. Ahipriya observes:“A worker who cannot read a summons sent to him, who is told by the police to ‘go home and settle’, does not see the law as a resource, he sees it as a threat. That fear is justified.” On the comprehensive framework, he points out, “India has the most comprehensive statutory framework to protect the poor in the developing world. But a right that cannot be enforced is not a right. It was a promise that was never kept.”For daily wage earners, a missed workday can mean a missed meal. So multiple court dates can translate into financial hardship, discouraging people from pursuing even legitimate claims.

Can legal aid help alleviate poverty?

Adv. Abhipriya points out that legal aid, when delivered effectively, has an immediate, tangible impact. The process is more direct than people assume:A woman who was illegally fired saved her family’s food security for months when she recovered her wages through a legal aid lawyer. Similarly, when a family gets a stay against illegal demolition, the children stay in school.He added that legal aid, when delivered well, is poverty alleviation, without the label of a welfare scheme.Between 2015 and 2025, more than 1.61 crore citizens received legal aid, while more than 40 crore cases were disposed of through the National Lok Adalat and the Legal Aid Defense Advisory System disposed of nearly 8 lakh criminal cases in three years.Government funding for NALSA for 2022-23 was Rs. 190 crore, which increased to Rs. 400 crore for 2023-24, down to Rs. 200 crore in 2024-25, and again by 25 percent to Rs. 250 crore in Union Budget 2026-27.However, structural challenges still remain:Awareness: Judges and legal experts stress that many eligible people do not know about free legal aid, with most assuming that they cannot get aid because it is unaffordable.Quality: Justice Nagarathna emphasized that “Poor legal aid is not poor legal aid.” Panel lawyers are often junior, overloaded and inadequately compensated. A wide disparity remains between legal aid representation and personal representation. This is not a criticism of individual lawyers but a systemic design failure.Geography: Tribal families in remote areas are often unable to reach district legal service authorities and the digital divide creates additional barriers to access online portals.Use of funds: Hon’ble Chief Justice Surya Kant revealed in the conference that by September 2025, only 16.93% of the legal aid and advice budget had been utilised, while the outreach expenditure was more than its allocation. Representation and aid distribution remain underfunded, while funds for awareness are overspent, which is contrary to priority.

Why this conversation is important

On World Social Justice Day, observed annually by the United Nations on February 20, the global spotlight turns to poverty, inequality, exclusion and human rights. For India, this underscores the urgent challenge of bridging the gap between legal rights and actual access to justice.As harsh as it may sound, society often reserves status for those who are rich and demands subordination from those who simply struggle to survive, educate and aspire. Poverty doesn’t just deprive, it silences. Understanding how poverty intersects with legal vulnerability is essential not only for policy reform but also for securing democracy. Because access to justice is not just another welfare benefit, it is the basis that determines whether rights exist only on paper or in reality.