‘From arsh to farsh’: Mani Shankar Aiyar’s ‘Rahulian’ outburst and ‘uncle’ syndrome | India News

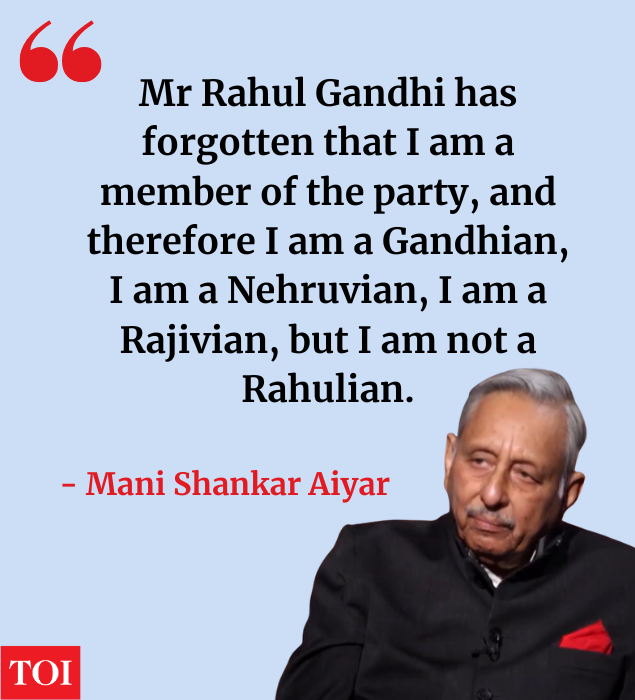

New Delhi: When senior leader Dr Mani Shankar Iyer Declaring that he is a “Gandhian, Nehruvian, Rajivian but not a Rahulian,” it sounded, at first glance, like another bout of his familiar provocation. But the comments, delivered in between CongressAttempts to project order and unity ahead of key assembly elections quickly raised wider debates about ideology, authority and dissent within the grand old party.The Congress quickly distanced itself from Aiyar’s comments and said the leader had nothing to do with the party. But was Aiyar merely indulging his taste for rhetorical rebellion, or was he hinting at something real about how the Congress had changed “under”? Rahul Gandhi?

Political analyst and Congress historian Rashid Kidwai believes there is “a grain of truth” in Aiyar’s claim, but not in the way the former minister envisioned.

Also read: Mani Shankar Aiyar is back and Congress ducks for cover again

‘Civil society’ politics since Nehruism

“There is a grain of truth in what Mani Shankar Aiyar is saying because the Congress has changed the Nehruvian ideology of seeing things or so called a civil society,” explained Kidwai.

Rahul Gandhi has no clean slate. Three, four uncles are watching him.

Rashed Kidwai

According to him, this change did not happen overnight. The Congress, he argues, passed through three distinct ideological phases.“What was Nehruvian thinking… Congress has moved from Nehruvian to economic reforms and from economic reforms, which were during Narasimha Rao and Manmohan Singh Rao, it has now moved to a civil society way of thinking,” he says.

This shift, Kidwai argues, helps explain why Aiyar’s attack on “Rahulian” politics resonates in some quarters. Congress under Rahul Gandhi does not operate within a rigid ideological framework in the classical sense.“So what you see around Rahul Gandhi are people from civil society and they are influencing him. So civil society doesn’t have a dogma,” Kidwai said.This absence of doctrine, he suggests, has consequences for how the party responds politically. Unlike the Nehruvian era, where ideology shaped policy, or the reform years, where economic realism prevailed, today’s Congress often appears reactive and issue-driven rather than programmatic.

The ‘Jai Jagat’ effect

Kidwai has previously written about what he describes as a growing “civil society” impression within the Congress, especially around Rahul Gandhi. This way of thinking, he argues, is based on moral reasoning, decentralized activism, and individual agency over state-led or party-led political action.This orientation, which gained visibility during the Sonia Gandhi-led UPA years through bodies such as the National Advisory Council, has now “almost taken over the party organization under Rahul Gandhi,” Kidwai writes.

The civil society hero, often associated with the so-called “Jai Jagat” group, is said to enjoy closeness to Rahul Gandhi and occupy influential organizational roles. Their emphasis on simple living, minimalism and symbolic politics became part of the contemporary Congress aesthetic.Yet, as Kidwai points out in his earlier writings, this culture sits uneasily with traditional Congress leaders who have risen through the ranks and understand politics as negotiation, organization and power management rather than moral cues.

Iyer’s isolation within the Congress

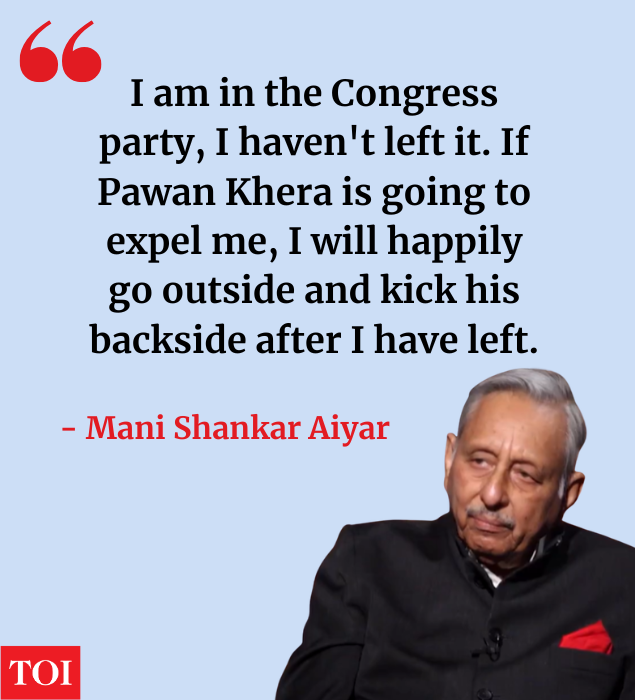

While Aiyar positions himself as a defender of Congress ideology, Kidwai is tight-lipped about his position within the party.“Manishankar Iyer feels that he represents the ideology of the Congress, be it panchayats or foreign policy or socialism which tends towards the poor… That’s not good. So there is no taker for Mr. Iyer,” Kidwai said.“Mr. Iyer is completely isolated. There is no group, no leader in Tamil Nadu or outside who subscribes to Mr. Mani Shankar Iyer,” he added.Kidwai contrasts Aiyar’s isolation with that of other Congress leaders who have disagreed with Rahul Gandhi but retain organizational traction.“Shashi Tharoor and many others still have some traction in the Congress… Manish Tiwari and many more. But there is no one who supports Mani Shankar Iyer,” he says.Iyer’s paradox, Kidwai argues, lies in his political identity. “Manishankar Iyer’s claim to fame was his loyalty to Rajiv Gandhi,” he says. “There is some opposition now that he is facing Rajiv Gandhi’s son,” Kidwai added.That conflict goes to the heart of Iyer’s frustration.

Dissent, Discipline and the ‘Uncle Syndrome’

Aiyar once again claimed that Congress of yesteryear tolerated the rebels while today’s leadership is punishing them. But is it true?“In most political parties, when adversity hits them, they split,” he says, recalling the splits in the Congress after 1967, 1969, 1977, and during and after the Narasimha Rao years.What makes the post-2014 period extraordinary, Kidwai argues, is not intolerance but tolerance.“What happened from 2014 to 2024, and now it’s 2026, is very unique, because there was a long spell of adversity, but no split. 150 leaders left, but there was no split in the Congress,” he said.

The result is a team carrying the baggage of multiple generations of leadership.“Rahul Gandhi does not have a clean slate. He has three, four uncles watching him,” Kidwai said. “Mani Shankar Iyer is the uncle who says – you are not doing anything right.”Also read: Grand Old Party Crisis – Why Are Congress Leaders Splitting?Iyer’s anger is deeply personal. “He felt that during Rajiv Gandhi’s time, he was ‘arshe’, which means cloud line. And he has come to ‘farsh’ (ground),” he says.Iyer, he added, had not adjusted himself to his reduced access to the Gandhi family. “He’s very hurt and angry about this whole thing,” Kidwai said.

Why did Congress ultimately draw the line?

Aiyar has repeatedly lambasted the Congress for his “chaiwala” and “neech aadmi” remarks. The recent explosion was nothing new. So after all these years has the Congress acted now, clearly stating that it has nothing to do with the party? The internal equation for Kidwai is responsible for the change.“There was a perception that Mr. Sam Pitroda and Mr. Manishankar Iyer are close to the family,” he says. That perceived proximity once served as an insulator.But that cover, Kidwai argues, has disappeared. “Now people know that his family doesn’t have support. So Mr. Iyer had a false cover… Now that has been exposed,” he said.In contrast, Kidwai notes, Pitroda remains protected. “Mr. Sam Pitroda is still in Rahul Gandhi’s good books, so nobody says anything about him,” he said, though according to Kidwai, both men were “motor mouths” whose comments often “hurt the political interests of the Congress.”

Spin doctor without a party

Kidwai traces Iyer’s penchant for provocation to his past.“Before the social media and internet boom, Mr. Mani Shankar Iyer was a real spin doctor,” he said, recalling Iyer’s diplomatic career and his role as a key aide to Rajiv Gandhi.That instinct, Kidwai argues, remains intact, but now operates without institutional context.“He is trying to get the attention of Sonia Gandhi and Rahul and Priyanka … and he is not getting it,” Kidwai said.Iyer’s use of the term “Rahulian”, Kidwai believes, is part of this attention-seeking strategy rather than a serious ideological intervention.“He has the ability to give spin, and that’s what he’s doing,” Kidwai said.But is there any truth to Iyer’s warning?While dismissing Iyer’s influence, Kidwai does not completely reject his diagnosis.“There is an uneasiness, which is not clear,” he says, referring to unease within the Congress over Rahul Gandhi’s reliance on civil society inputs rather than organizational consensus.He cited campaign slogans and movements like “Chowkidar Chor Hai” and “Vote Chori” as examples of tactics that did not emerge from internal party discussions.“None of these things came from the Congress organization,” Kidwai saidYet, unlike Shashi Tharoor, who got 11-12 percent of the votes in the 2023 Congress presidential election, Aiyar was not followed.“Mani Shankar Iyer will get zero,” Kidwai said vaguely.For now, Aiyar has coined the new term “Rahulian” that Congress opponents may try to stick in public memory. Its promoters, however, may have further faded into irrelevance.Iyer may have named something real, an ideological shift from structuralism to civil society politics. But in doing so, Kidwai argues, he has personalized a transformation that is bigger than Rahul Gandhi and older than Aiyar’s own allegations.In the end, Aiyar’s rebellion says less about the future of the Congress than a veteran’s inability to move on without the party he once built.