Who after Vijayan? Left’s tryst with first-time voters and survival in Kerala | India News

as Kerala Heading into the 2026 assembly elections, one question hangs over the state’s political landscape: What does the future of the Left look like beyond? Pinarayi Vijayan?For nearly a decade, Vijayan has been the undisputed face of the Left Democratic Front (LDF), weathering floods, pandemics, financial pressures and, in 2021, a historic re-election that broke Kerala’s four-decade pattern of alternating governments. But as the chief minister approaches 81, the conversation among party ranks and voters has quietly shifted from governance to succession.

Kerala is currently the only state which is ruled by the Left. This makes the 2026 election more than a routine contest; It is a referendum on the future of communist politics in India and whether the LDF can renew itself in time to connect with a new generation of voters.

Vijayan Factor: Age, Authority and Continuity

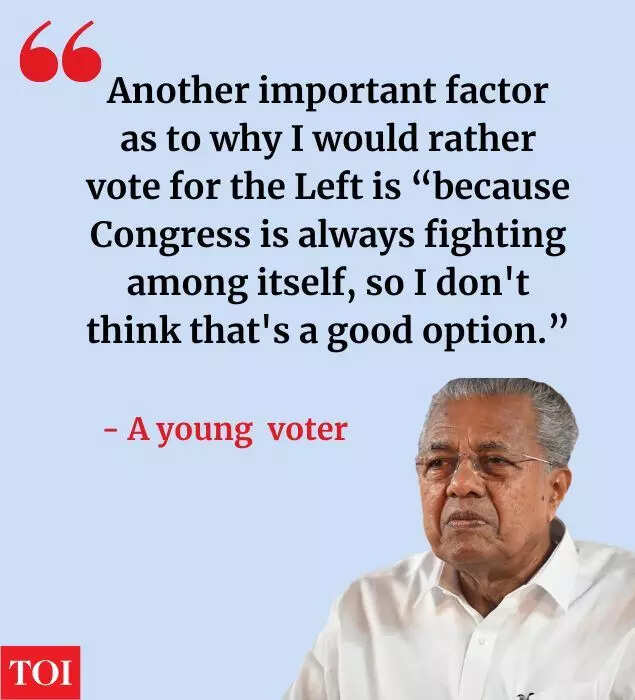

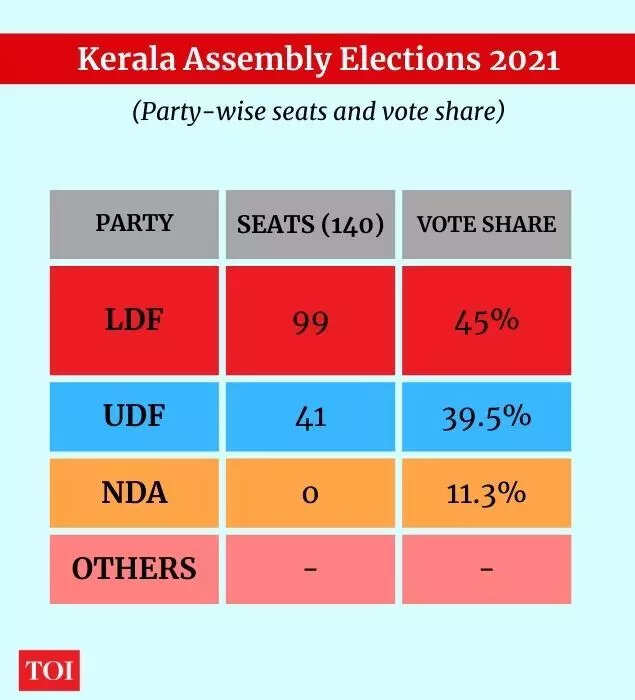

At 80, Vijayan remains the central pivot of the LDF’s campaign and governance narrative. His leadership was widely credited for the LDF’s 2021 victory, when the front won 99 of the 140 seats, returning an incumbent to power in Kerala for the first time in four decades.The government has since highlighted welfare expansion, including raising the social security pension from Rs 600 to Rs 2,000, infrastructure spending of around Rs 2 lakh crore through the budget and extra budget, and a push towards a “knowledge economy”.Still, the question is less about performance and more about consistency. “Leadership transition is a structural problem for cadre-based parties,” said the Delhi University political science professor “The Left’s strength has always been collective leadership, but electorally, voters in Kerala are increasingly responding to recognizable faces.” Sherwin, a young freelancer from Delhi-based Thrissur, believes, “If not for Vijay, the Left will probably not come back to power.” He cited another important reason why he would vote for the Left: “Because Congress is always fighting among itself, so I don’t think it’s a good option.”He added, “It’s always the least worst option that you vote for, not the best, which is what happens in politics, I think, everywhere now.”

Dhrishi, a member of a left student group, said, “Vijayan doesn’t look that bright, maybe there is no one to replace him at the moment, but that doesn’t make him good.” He added, “I think it’s time that more young faces are given a chance, just look at the Politburo, the people sitting there have nothing to do with the soil and the kind of problems that the youth are facing.”

Missing second episode

Unlike previous phases in Kerala politics, no widely projected young leader was positioned as Vijayan’s natural successor. Although a number of senior ministers and party leaders remain influential within the Communist Party of India (Marxist), the LDF’s major partner, none currently wield statewide mass appeals comparable to that of the Chief Minister.Projecting a successor ahead of time could create factional tensions, said a member of the left-wing student body. “The party prefers continuity and collective action. Focus on principles, not personalities,” he said.

But electoral politics is increasingly personality-driven. The absence of a clearly visible next-generation face could complicate reaching out to first-time voters, especially in urban constituencies where the three-way contest is sharpening, with a growing BJP/NDA footprint.

First time voter: A variable voter

The criteria for the youth electorate is becoming clear. According to government figures cited by AIR News after the release of the draft voter list for the state, over 1,21,000 applications for updates and corrections have been received. Of these, 96,785 were submitted to include first-time voters who were 18 years of age or sought electoral transfer. For the LDF, engaging Gen Z voters presents both opportunities and challenges. This population has grown up in a hyper-connected political environment, shaped by social media narratives as much as traditional cadre networks. Increasingly, these first-time voters have become the most sought-after political entity that every party wants to govern on their behalf. “For us, development and jobs are more important than ideology,” said Vishnu, a 22-year-old first-time voter from Alappuzha studying in Delhi. We want to see opportunities in the state so we don’t have to leave Kerala.” Another student from Kozhikode points out that while welfare measures are important, “the conversation online is different, people talk about entrepreneurship, start-ups, global exposure.”The LDF has responded with a renewed focus on digital outreach alongside its traditional house-visit programme, where leaders, from state-level figures to branch secretaries, engage directly with families to gather feedback.But Sherwin said, “While the Left has a very active youth group working for it and they always come up with different plans, Congress does the same, so I don’t see anything different in what they’re doing to attract the youth.”

Local Body Elections 2025

If the 2021 assembly verdict was historic for the LDF, the 2025 local government elections are a reality check.The scale of the damage was significant. The LDF’s control in gram panchayats fell from 577 to 340, in block panchayats from 111 to 63 and in zilla panchayats to 11. In urban Kerala, the slide was even sharper: municipal corporations under LDF control fell from five to one, while municipalities fell from 43 to 29.The most symbolic blow came in Thiruvananthapuram, where the BJP captured the corporation for the first time, winning 50 out of 101 wards. For a front that had dominated the capital’s civic body since the 1980s, the political weight of the defeat was beyond numbers.However, vote share data tells a more nuanced story. Despite losing seats, the LDF polled nearly 40% of the statewide vote. The UDF secured 43.21%, maintaining a lead but not a landslide margin. The BJP-led NDA’s vote share was around 16%, slightly higher than in previous local elections and lower than its 19.4% performance in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections. Party gains have come from concentrated seat shifts rather than dramatic vote expansion.In terms of assembly segments, the UDF is leading in 81 seats, while the LDF is leading in 57. However, in 32 seats, the LDF’s margin of defeat was between 1,000 and 10,000 votes, indicating that micro-swings could reshape the 2026 map.There was also a demographic undercurrent. With minorities constituting almost half of the state’s population, the LDF’s vote share of around 40% indicates that it retains a significant chunk of minority voters as well as other segments, even as segments are seen consolidating behind the UDF in parliamentary-style contests. The data indicate change, but not decline.From the perspective of the left, local agency judgments reflect three trends:

- Sharp triangular competition

- More efficient seat conversion by UDF and BJP, and

- Vulnerability in pockets of the urban middle class, especially among young voters

Whether the 2025 results were a precursor to 2026 or a mid-term correction remains an open question.

In welfare and perception

The DU professor argues that anti-incumbency alone does not explain the LDF’s recent debacle. Instead, “electoral changes reflect layered dynamics, consolidation of minority votes behind the UDF, sharp arithmetic in urban areas and targeted expansion of the BJP”. Adding, at the same time, it seems that, after two consecutive terms, the LDF is redefining its political messages amid demographic and ideological churn.

That realignment became visible to the world during the conflict over Jamaat-e-Islami Hind. D CPM And the BJP has accused the Congress-led UDF of taking support from the outfit. The controversy escalated when senior CPM leader AK Balan warned that a UDF government could allow Jamaat influence in the home ministry and lead to incidents like the 2002-03 Marad riots. CM Vijayan supported Balan’s comments, though the CPM later described them as his “personal views” following criticism that the speech echoed the narrative usually associated with the Sangh Parivar. But, the incident was uncharacteristic of the Left, which has largely avoided entering the arena of communal/polarizing rhetoric as compared to the country’s political landscape. Simultaneously, the Left has moved to strengthen ties with sections of influential Muslim organizations such as Samath, including by nominating Umar Faizi Muqam to the Kerala State Wakf Board, a move widely interpreted as a calibrated engagement with constituencies seen as separate from the IUML.On the majority side, the government’s role in facilitating the Global Ayyappa Sangam linked to the Sabarimala temple, run by the Travancore Devaswam Board, drew attention due to the Left’s earlier strong support for the 2018 Supreme Court ruling allowing women of all ages to enter. Meanwhile, with the elections looming and the Sabarimala snowball a larger electoral issue, the Left is taking an increasingly ambiguous stance, with its ministers refusing to give any direct clarity.

Taken together, these episodes reflect the LDF’s efforts to navigate a more polarized landscape by balancing welfare governance with identity-sensitive politics as it prepares for 2026.

The Revival Playbook

Party leaders acknowledged the need to “learn from the people” and correct gaps in policy implementation and political communication. Statewide home inspection program has been launched. In parallel, the LDF intensified its campaign against fiscal disparity at the Centre. Issue-based mobilization is being sharpened with MGNREGA allocation and labor code implementation campaigns. But the deeper challenge is the political stance. At the root of the historical growth of the Left in Kerala was stratification between caste and religion. Recent elections have revealed tensions between welfare-driven governance, secular stances, minority concerns and broader social mobilization efforts. A sustained revival may require clarity in ideological messaging as much as administrative skill.The revival question, therefore, is less about arithmetic and more about adaptability.

What’s next for the left?

For the Left, 2026 is not just about holding on to power, but about redefining relevance. Baji National: Kerala is the last state under communist rule. A defeat would mean the absence of a Left-led state government anywhere in India.The immediate strategy appears to be two-fold: mobilizing welfare beneficiaries through grassroots engagement and countering opposing narratives through concerted political campaigns and social media mobilization.But the structural question remains unresolved: Can the LDF transform from Vijayan’s authoritarian leadership model to one that inspires confidence among young voters?As Kerala’s electorate expands with thousands of first-time voters, the 2026 contest may depend less on legacy and more on generational trust. Whether the Left can bridge that gap organizationally and politically will determine whether its red base remains intact or enters a new phase of churn.The question, for now is simple and inevitable: Who is after Vijayan?